The ongoing pandemic is fertile ground for opportunistic hucksters, loud frauds, and coronavirus deniers who attack or blame everyone from Chinese Americans to Bill Gates to 5G networks. The latest front in this bizarre war: Contact tracing.

Tracing is the technique used by public health workers to identify carriers of an infectious disease and then uncover who else they may have exposed, in an effort to isolate those at risk and halt the spread of an outbreak. It’s a time-tested investigation method used to successfully fight outbreaks of diseases including measles, HIV, and Ebola. Countries around the world are using it against covid-19 already with great success, and now many states around the US are beginning to assemble their own covid tracing teams. At the same time, powerful technology companies including Apple and Google are building systems to help expand and automate tracing and notify people of possible exposure. Yet contact tracing—like testing, social distancing and isolation—is now caught in the political crossfire.

“That’s totally ridiculous,” Rudy Giuliani told Fox News host Laura Ingraham when asked about New York’s plan to hire an “army” of coronavirus tracers. “Then we should trace everybody for cancer and heart disease and obesity,” he mocked. “I mean, a lot of things kill you more than covid-19, so we should be traced for all those things.”

“Yeah,” Ingraham snorted, rolling her eyes. “An army of tracers.”

Virtually all medical professionals—and authorities from America’s Centers for Disease Control to the World Health Organization—emphatically say contact tracing is a crucial part of the three-pronged plan for returning the world to normal: test, trace, isolate.

“I don’t think we can overstate the importance of contact tracing,” says Seema Yasmin, director of the Stanford Health Communication initiative, and a former CDC investigator focused on epidemic outbreaks. “It’s been at the cornerstone of every major epidemic investigation to SARS to Ebola and beyond.”

While testing is the absolute top priority—you have to find the people who are infected, after all—tracing is vital for stopping a disease from spreading out of control. Once you have identified those at risk, you put those people in isolation before they too can spread coronavirus further.

“Coronavirus has a weakness because the typical transmission time is fairly long, about a week,” says Microsoft’s John Langford, who has been working with the state of Washington on its contact tracing efforts. “If you can trace this in smaller time scales, you can shut it off.”

But while Giuliani’s statement is painfully inane—obesity, for example, is not an infectious disease—the truth is that contact tracing efforts in this pandemic do face historic and very real challenges. Whether it’s done manually by teams of investigators or automated through phone alerts, tracing has never been done at the scale needed to fight covid-19. All of the genuine problems and concerns around tracing will be exacerbated, and they will need to be addressed if these efforts are going to succeed.

Here are five things that need to happen to make contact tracing work in the US.

Task 1: Hire 100,000 manual tracers

Once the country begins to re-open, but before there is a vaccine or effective treatment, the primary way of preventing the spread of covid-19 will be manual tracing. Trained medical workers get in touch with those who are diagnosed with covid-19 and collect data about their movements and contacts. A patient may have been in contact with 100 other people recently, which means 100 follow ups by phone or in person to track down everyone at risk of exposure. Depending on the data and science, tracers may then request isolation and tests. It’s labor intensive work.

“This is going to be a massive undertaking,” New York governor Andrew Cuomo said at a press conference last week.

His state, and New York City itself—now the hardest-hit region in the world—showcases the difficulties that America has had with building manual tracing capacity. A metro area with a population exceeding 21 million people and over 16,100 covid-19 deaths has had fewer than 1,000 tracers in action so far (compare that to 9,000 tracers in Wuhan, a city of 11 million.)

American health departments have been chronically underfunded since the 2008 financial crisis, losing more than 55,000 workers despite repeated warnings of the risk. In fact, there are currently only 2,200 contact tracers in the entire United States, according to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

That is now changing. New York is working with New Jersey and Connecticut at a regional level, and hopes to tap into the talents of thousands of medical students, while Massachusetts has budgeted $44 million to hire 1,000 contact tracers. San Francisco was one of the first local governments in the nation to begin building its contact tracing team, which could ramp up to 150 people monitoring a city of 880,000; California governor Gavin Newsom has promised 10,000 more across the state. But all this is merely a start.

A recent report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security said as many as 100,000 workers may be needed to make manual contact tracing efforts effective across the country. And to get there, Congress needs to spend around $3.6 billion. Former CDC director Tom Frieden, who believes the cost could be even higher, recently said that the same approach is needed all around the country.

Task 2: Protect privacy

This is where automated tracing becomes appealing. The concept, which uses technology like Bluetooth and GPS to automatically determine whether a person may have been exposed rather than rely on manual tracing, has been put in the spotlight as authorities around the world try to cope with the astonishing rate of covid infections.

“We will remain vigilant to make sure any contract tracing app remains voluntary and decentralized”

Jennifer Granick, ACLU

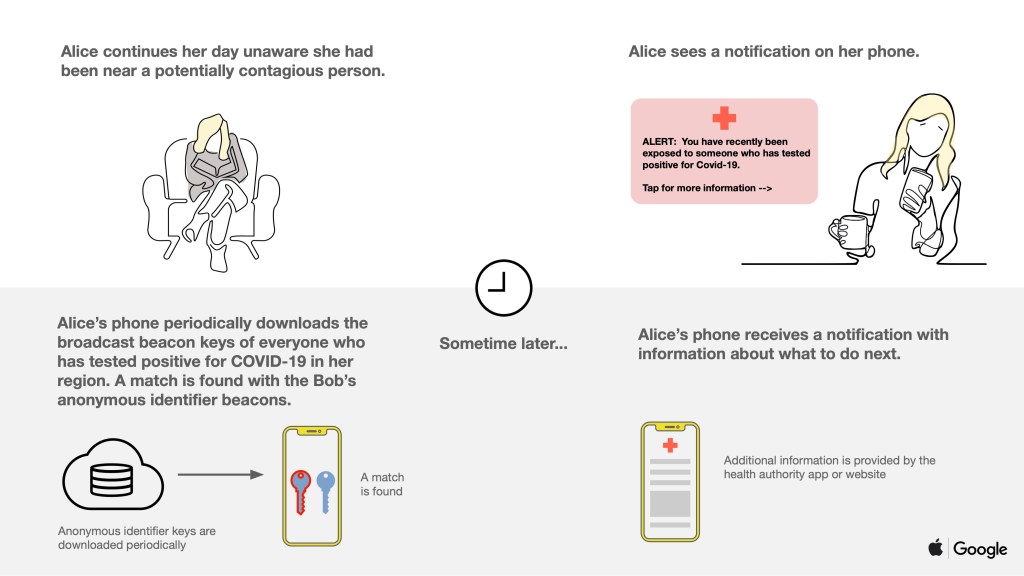

High tech efforts—especially in Asian countries like China, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea—have generated many headlines, but when Apple and Google release their system for building exposure notifications into their own smartphones, it will be the most significant development globally. The two companies are responsible for the software on more than 99% of phones on the planet, and eight out of 10 Americans own a smartphone. By building the system directly into iOS and Android and making them interoperable, apps using their systems could dramatically increase the reach of the public health authorities in one swoop.

But the technologies themselves have a number of issues, and privacy advocates and civil liberties campaigners have valid concerns about the use of such systems. Contact tracing is a form of surveillance that, in the worst case, can be abused by companies or governments. Medical surveillance has repeatedly proven to be a life-saving tool, however, and Apple and Google say they are making privacy a priority by building decentralized systems that can be resilient against malicious surveillance and enforcing best practices while also providing key data to public health authorities. This is all new and highly reliant on the actions of governments themselves.

“To their credit, Apple and Google have announced an approach that appears to mitigate the worst privacy and centralization risks, but there is still room for improvement,” Jennifer Granick, the surveillance and cybersecurity counsel for the ACLU said when Apple and Google announced their tracing technology. “We will remain vigilant moving forward to make sure any contract tracing app remains voluntary and decentralized, and used only for public health purposes and only for the duration of this pandemic.”

Task 3: Ensure tracing covers as many people as possible

But those building automated services are keen to stress that they are not trying to replace manual tracing, they’re trying to aid it. They see digital tools as a way to complement and scale the work done by human teams. For example, smartphone alerts can help filter out those at low or no risk so that manual tracers can spend their time investigating genuine cases. Or, instead of spending time and energy chasing down everyone by hand, automated alerts free up resources so that manual tracers can reach those who are more at risk or harder to contact.

“Our philosophy is that contact tracing is essential to shutting down the epidemic and having an economy that works,” Microsoft’s Langford said. “With digital tools, we want to enhance the process of contact tracing. The primary thrust is manual contact tracing. But there are things we can do with a phone app which makes this work more effectively.”

But even if a tracing app was downloaded by everyone who could legitimately use it, a major challenge for smartphone tracing globally is the simple fact that not everyone owns one. If eight out of 10 Americans own a smartphone, that means two out of 10 don’t. Highly vulnerable groups are frequently on the wrong side of that digital divide, says George Rutherford, professor of epidemiology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Only 42% of Americans above the age of 65, the same group that makes up eight out of 10 deaths from covid-19, own a smartphone, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center poll.

In San Francisco, some of the biggest case clusters are among the city’s homeless and Latinos, populations in which smartphone ownership rates also lag. About 40% of the potentially-exposed people that the city’s contact tracing effort has reached are monolingual Spanish speakers, many of whom live in crowded multigenerational households.

Rutherford said that both smartphone ownership levels and immigration status could discourage them from using apps that track their movements. Indeed, at least one San Francisco health official has said that fear of immigration authorities is discouraging participation in the city’s manual tracing efforts as well.

“If you’re here or Texas or New York, places with large immigrant populations, with ICE breathing down everyone’s neck, the last thing they want is their information in a database,” Rutherford says.

This is an area where human tracers who can establish trust will be key.

“You need to make sure those people represent the communities that they are going into,” says Stanford’s Seema Yasmin. “It’s so important as you do contact tracing that it’s thorough—meaning that people trust you, that they do give you the information you really need to do it to its fullest extent. If people are already frightened about the way that immigrants are being treated during this crisis, because of the legislation and rhetoric, then you want to make sure that you send the right people into communities where there are lots of immigrants, whether they’re undocumented or not, to make sure that people feel like they can trust you and can be honest with you.”

You can’t get away from the need for strong, careful manual tracing. But it turns out that even in countries that have been noted for using high-tech tracing methods, the reality on the ground is actually very human.

Task 4: Don’t rely on technology alone

In Taiwan, fears of the virus were extremely high very early on in the outbreak. More than 850,000 Taiwanese citizens live in mainland China, and they routinely travel back and forth between the two countries. So far, however, there have been just 428 confirmed cases and six deaths from covid-19. Much media coverage focused on the high-tech methods deployed by the government—for example using cellphone signals to track the location of people in quarantine and make sure they were staying inside.

But in fact, efforts have mainly been a mix of high and low tech measures. The country closed its borders to foreign citizens arriving from China on February 7, and to all non-citizens on March 19. Even those who came back had to undergo a 14 day isolation at home.

Brandon Yu, a Taiwanese student at Brown University who returned to Taipei in March, says that every day during his quarantine he had to note down his temperature on a piece of paper and respond to phone calls from his public health office. “They were super short,” he says. “‘How are you doing? Get some rest, I’ll call again later.’” On the first call they reminded him that his location was being tracked, and that even his phone running out of battery—which stops it pinging nearby cellphone towers—could result in police or health officials knocking on his door.

If a patient is confirmed to have covid-19, they are required to stay at a hospital until they recover (something that is only possible because Taiwan has so far avoided its health system being overwhelmed.) Dr Haoyuan Zheng from the Taiwanese CDC says that while researchers can request patient’s cellphone location data, it has not actually been very helpful: “Covid-19 spreads through close contacts, for example within a household or in a classroom,” he says. “Usually, these are people that patients have spent a lot of time with and who they know personally.” To date, Taiwan has not employed any automated contact tracing apps.

It’s true that China leaned heavily on tech, partly aided by invasive and mandatory data sharing enforced by the government. But Wuhan also had thousands of human contact tracers making calls to patients and contacts, compiling data, and tracking down others who are at risk, not to mention strict policies governing movement during lockdowns.

Meanwhile in Singapore, where the TraceTogether app broke ground as the first government-backed automated tracing service in the world, only 10-20% of the country actually uses it.

“People are confused about the way these areas work thinking they are entirely automated,” said Sham Kakade, a research scientist at Microsoft working on contact tracing. “There is automation but there are humans in the loop in all of them. The humans are playing detectives.”

All of these countries have a toolbox of policies and approaches that help them investigate coronavirus cases. In Singapore, one of the lead developers of TraceTogether made his feelings on the subject extremely clear.

“If you ask me whether any Bluetooth contact-tracing system deployed or under development anywhere in the world is ready to replace manual contact tracing, I will say, without qualification, that the answer is, ‘No,’” he wrote. “Any attempt to believe otherwise, is an exercise in hubris, and technology triumphalism. There are lives at stake. False positives and false negatives have real-life (and death) consequences. We use TraceTogether to supplement contact tracing — not replace it.”

Task 5. And do it all, now

Even if the likes of Rudy Giuliani scoff at the need for “armies” of tracers, and even if genuine concerns about adoption, accuracy, trust, and funding remain, every expert agrees: Contact tracing is needed, it works, and doing it well will not be easy.

More people may well be needed to make this happen. Johns Hopkins’ estimate of 100,000 tracers nationwide may need to rise if the virus spreads further; even Google and Apple’s automated service will require many thousands of health workers to conduct verified testing and follow-ups.

Doing contact tracing well, at the volume required to tackle the disease, will require not just lots of people working on manual tracing and automated efforts, but also plenty of money and a lot of coordination. A program of test-trace-isolate requires knowing where the coverage gaps are, who’s affected, what those people need, and what it takes to reach them.

And for now? Don’t wait.

George Rutherford at UCSF said his team in San Francisco will take a harder look at the potential of any emerging apps to reduce the workforce required a few weeks down the road. But for him, the focus for now is rapidly building the sort of traditional, human-powered contact tracing effort that has worked to contain outbreaks in the past.

“We’ve got to really understand exactly what we’re doing, who the people we’re dealing with are, what their concerns are and what works best in identifying and isolating infections, and quarantining those who may have been exposed,” he says. “That’s the name of the game.”

—Additional reporting by James Temple and Katharin Tai

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/3aNB1IC

via IFTTT

Post a Comment