The police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were sparks that reignited smoldering fury against authorities across the globe. One of the most watched locations has been Seattle, where protestors barricaded off a cop-free zone, drawing outsize attention and, in the process, forming a new case study in the uses of technology both to advance a cause and to drown it in disinformation.

From the actual recording of Floyd’s killing and the protests and riots that followed, to documenting the police’s brutal response and sudden withdrawal, to the establishment of and widespread commentary on an improvised community, technology has played a crucial role throughout. But to center things properly, it is how people are using technology, not the technology itself, that has become more important.

More than ever before, information truly is power, and imbalances in who holds that power have been both reinforced and challenged in the course of events here. It’s heartening to see live streaming and instant distribution of video lead to accountability, but it’s also sickening to see deliberate campaigns to manipulate and subvert reality — and I say reality because it’s what I’ve seen with my own eyes.

As a brief preamble, I should disclose some things.

First, I support the causes being advanced by protestors in Seattle. It would be useless to deny that I have taken sides here — partly because claims of objectivity are little more than a fig leaf for editorial decisions in matters of grave injustice and obvious abuses of power; but my presence at the protests has unavoidably been documented whether I like it or not, so there’s no sense in denying it.

Because second, I live on Capitol Hill, just blocks away from the zone. I’ve been eyewitness to important events, (with a built-in tech angle at that) and it would be irresponsible for me not to use the privilege of this platform to share aspects of them that have been only sporadically covered.

And third, these protests have been organized and led by people of color, and I am a white guy who, comparatively, has only barely taken part. On issues of race, policing, and inclusion I will defer to others better equipped to educate: writers like Ijeoma Oluo (whom we recently interviewed), researchers like Joy Buolamwini, and publications like Blavity.

With that out of the way, this article will focus on three topics: The collection and use of digital media on both sides of police clashes; the use of social media and battle of information versus disinformation in the cop-free zone; and the emergence of live streaming as an indispensable medium for this and future movements.

A matter of perspective

The initial protests in Seattle in late May, which devolved in some locations into riots involving the despoliation and destruction of police cruisers (somehow left unattended and filled with weapons), are difficult to track because they were full of movement and chaos. But they were thoroughly, if haphazardly, documented by attendees with the presence of mind to record what they were seeing.

It’s telling that there has been little or no attempt at a counter-narrative from Seattle authorities when their officers were repeatedly (and continually as of this writing) filmed employing plainly excessive force against unarmed, often unresisting protestors, or indiscriminately firing tear gas, pepper spray, and flashbangs into crowds. One woman’s heart stopped three times after being struck by a blast ball that appeared to be deliberately aimed at her, while thousands watched.

Where, one wonders, is the exonerating footage from the police side showing the protestors being described as aggressive, or non-compliant, or whatever key words officers use to justify brutality during a melee of their own creation? And yet the police are at a loss. Presented with innumerable examples of bad behavior, the force seems to have decided day after day to stand fast and let it blow over.

But it’s hard to do that when you have something like a video going viral of a child who’s been maced:

This image, which came to represent the Seattle PD’s inhumane treatment of protestors (they stand by wielding batons as the crying kid is treated), was taken by a local named Evan Hreha. It’s hard to erase such a powerful image — so they arrested him.

Hreha was arrested a week later by a dozen officers and booked into jail for, supposedly, pointing a laser at police. It hardly needs to be said that this account strains credibility. For one thing, Hreha says he was running a hot dog stand with friends at the time of the alleged offense. But it is absurd that police would or could identify one person in a crowd at a distance, then investigate and arrest them — for anything, let alone a fleeting non-violent laser use. And it just happens to be the man behind a viral video that makes the cops look bad.

This seems to be plainly a case of retaliation, but the police have made themselves unaccountable by controlling the information available. I contacted the records department to ask for anything related to the investigation and arrest of Hreha (among others), but it will be months before the police will release anything, if indeed they ever do.

Hreha was released two days later with no charges filed. But the chilling effect of intimidating someone who caught police in an act of brutality on camera had been accomplished. The officer who maced the kid, incidentally, has yet to be officially identified or disciplined.

This is exemplary of the power imbalance in conflicts of this type: On one side, voluminous documentation from people on the ground that is disorganized and difficult to bring to bear; on the other, documentation that is carefully organized and tightly controlled, allowing the exertion of authority using that control as leverage. Police have also begun the process of repurposing news and protestor footage for their own purposes.

But this story doesn’t always play out the way the cops would prefer.

In the first week of June, protestors were marching up Pine to confront the police for this and other acts, after which they would have, like many similar protests, moved on to rally in Volunteer Park and then gone home, to do it again another day. But police blocked them at 11th and Pine with a barricade and line of police in riot gear.

SEATTLE, WA – JUNE 08: A person holds flowers as demonstrators clash with police near the Seattle Police Departments East Precinct shortly after midnight on June 8, 2020 in Seattle, Washington.

The group did not disperse as ordered, saying they would stay and protest peacefully until the police moved out of the way. Predictably, when curfew came, the police were liberal in their deployment of tear gas and flashbangs, causing serious harm to some protestors and terror across the entire neighborhood. This continued and grew in intensity for several days and nights. (In many cities these clashes are ongoing.)

The justification for using their “less lethal” tools with such gusto was predictable: The crowd was violent, throwing bricks and even improvised explosives at officers. But these claims were repeatedly and firmly dismantled, because these encounters were filmed in high definition from multiple angles, practically from start to finish.

One particularly revealing video was shot by a person on a roof directly over the barriers. It quite clearly shows a peaceful crowd chanting and definitely not throwing rocks and bottles. Anyone can review it and see that there was not only no violence on the part of protestors, but that the flashpoint moment occurred (documented in other videos as well) when a cop tore a now-famous pink umbrella from the grip of a person, who in offering any resistance provided the excuse for the police to retaliate — indiscriminately and utterly disproportionately.

Huge volumes of evidence of police brutality have resulted almost solely from the oft-mocked habit of young people to always have their phone in hand. (We’re not far from the always-recording situation I posited nearly 10 years ago.)

“They picked the wrong generation to pull this shit on,” said TK, a protest organizer I spoke with. “Because governments didn’t create this power — this was created by normal, regular-smegular people just like all of us. The only people that can stop it is the people that created it.”

Rarely have the police released images or footage of their own, and when they do it is often a brutal self-own. They posted images of the aforementioned “improvised explosive” on Twitter shortly after one group assault on protestors, and within seconds people had pointed out it was a prayer candle, probably from a nearby memorial smashed during the melee. The police revised their reference to it as an “incendiary device,” which, while technically true, exposes the type of willful obscuration of the truth that was frequently to be found in the department’s communications.

Following another incident, body cam footage was released to support the narrative that a “violent crowd” had prevented the police from reaching a shooting victim in the protest zone and were therefore culpable in his death. People soon pointed out that timestamps visible in the video show that the cops arrived 20 minutes after the shooting, and after the victim had been taken to the hospital in a private car — because EMTs (for good reason) would not enter the scene before police secured it.

When the police chief made claims of rape and violence in the protest zone, it was pointed out that the SPD’s own crime reports system showed no such thing. Then her claim that armed gangs were extorting local businesses was quickly put down as well, by the businesses themselves — embarrassingly, the source of that claim was a totally invented account on a right-wing blog. (Ironically, once the police retook the zone, businesses quickly complained that their presence had forced them to close.)

And of course there are the innumerable videos, here as elsewhere, of extreme force being used on unresisting protestors, frequently with the apparently now requisite knee on the neck. These will hopefully prove useful later as counterbalance to police claims, and while officers still obscure their badges and refuse to identify themselves, the quality of the video makes identifying them by other means trivial.

The digital record has resulted in officers, the department and the chief being caught in lie after lie after lie. These are not misunderstandings or honest mistakes but misrepresentations deliberately crafted to discredit protestors and shield the department. It’s clear that if others were not carefully documenting every encounter, and critically investigating police statements and evidence, the lies would have shortly become the only, and therefore the true, record of what happened.

What I’ve described took place in Seattle, but others have compiled abuses in L.A., New York, Portland, and Chicago — where cops have just been caught in another type of large-scale manipulation of the record.

Now in many cities these departments are facing cuts or total defunding, as much as the result of their failure to successfully falsify the narrative as their more fundamental failures as institutions.

“This generation is not dumb, as much as they want to believe that. ‘You guys are just a bunch of dumb kids.’ Okay, well, this bunch of dumb kids is about to get the city to take half of your budget,” said TK. “So we ain’t that dumb, apparently.”

A last example of the power of social media in the pursuit of problematic police came late in the writing of this piece. After two protestors were struck and one killed on a closed highway after a driver circumvented police barriers, a detective from the King county Sheriff’s office made several brutally offensive posts on Facebook — public ones.

These were spotted by concerned citizens, who took screenshots not just of the content but also the list of people who had liked or commented positively on the posts, looking them up, as well. This proved to be a shrewd tactic, for when the posts began to make waves online, Brown’s entire Facebook page was deleted.

Turns out Detective Brown is not only Governor Jay Inslee’s cousin, but reportedly also the head of county executive Dow Constantine’s security detail and his sometime driver; a 40-year veteran of the force who has been accused of abusive behavior before. Within 48 hours Detective Brown was on leave and being investigated. One hopes that the officers and public officials who publicly endorsed Brown’s behavior will soon be confronted, as well. But how quickly this avenue of recourse would have disappeared had they been tipped off.

Keeping the cops honest is a welcome application of what might be termed citizen forensics, but social media would soon provide a counter-example of technology being deployed to discredit the protestors and mislead millions.

In the Zone

Believe it or not, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone wasn’t anyone’s idea.

The now infamous cop-free area barricaded off by protestors has been profiled frequently and, almost without exception, incompletely and inaccurately, in mainstream news and on social media. It’s an instructive but deeply frustrating example of how, as the old saying goes, “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on.”

A very brief origin story is as follows: On June 8, following a particularly violent yet ultimately unsuccessful attempt to purge the area of protestors the previous night, the police abruptly announced they would be leaving the East Precinct building, taking all valuables, weapons, and sensitive documents with them.

Protestors were astonished. They had not asked for this and had no reason to — their demands were about defunding the police, investing in the community, and releasing jailed protestors. Incredibly, even now no one has taken responsibility for ordering the abandonment; the mayor and police chief have both denied doing so. But abandon it, they did.

Protestors immediately continued marching, some continuing to Volunteer Park and others remaining behind, citing the need to protect the precinct from anyone who might want to damage it, for days on end if necessary and at all hours. If you’re skeptical, remember: This is all on video. People learned early on that many people only believe what they have seen, and even then only sometimes.

Since a car had nearly plowed through protestors the previous day and the driver actually shot someone (before being gently taken into custody by police), and hearing reports of right-wing agitators in the area, the protestors redeployed the barriers to make a safe zone at the ends of nearby streets. Someone spray painted “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone” on one, inadvertently branding the whole movement.

What followed in the CHAZ (later the CHOP) was several days and nights of compelling events, speakers and tributes to lost lives, attended by thousands, including myself.

But what followed online was a nonstop deluge of wild exaggerations, manipulated media, racist vitriol and, of course, innumerable death threats. It would be impossible to list even a fraction of the information online that I could contradict with what I saw with my own eyes, but here are a few examples.

The most glaring one has to be, of course, Fox News photoshopping a gunman into multiple unrelated scenes of destruction and dishonestly using those as evidence of chaos in the zone. This was done so poorly it would be comical if it were not part of a larger, continuing narrative seeking to discredit the protests and zone as an antifa-run separatist state.

One of the images run by Fox News, a combination of one by David Ryder (whose photos for Getty illustrate this piece) with two by Karen Ducey.

The separatist narrative, which persists even today, was invented and amplified by lazy or traffic-hungry outlets and pundits with little evidence besides the tongue-in-cheek name.

There was not always the need to invent controversial imagery (indeed, the gunman Fox used really existed). Video of one person handing out rifles to his crew quickly made the rounds and, combined with the police chief’s irresponsible rumor-mongering, word of a “warlord” emerged.

Without getting into the complex and largely improvisational politics of the zone, this character and his heavily armed presence were generally not approved of. But for the weeks following this event I saw the image, his name and the warlord trope posted thousands of times, coming up every single day.

It’s tempting to say it’s hard to misconstrue a guy distributing assault rifles from the back of his car. But it is testament to the fractured narrative presented online that crucial context was almost always left out or substituted by falsehoods. Not only had a gunman actually shot a protestor after driving his car into the crowd the previous day, but at the very moment of the video, the police were suspected to have been engaged in a disinformation campaign intended to provoke conflict.

Public police scanner frequencies that night (which it was known protestors were monitoring) were full of reports of a group of 20-30 armed “Proud Boys” (a far-right group) moving toward the protest zone. Bike police on scanners said they followed the group for blocks, asked where they were headed (the CHAZ), tried to dissuade them from going there, and eventually reported that they spontaneously dispersed before reaching their destination.

Now, a large group of armed men working their way up from Downtown to Capitol Hill would be a rather conspicuous sight even in those days when record numbers of armed men walked the streets. Yet none of the thousands of protestors and allies spread throughout the city watching for them saw anything matching that description during or after. No communications from known Proud Boys (some of whom would in fact show up later to attack a protestor on video) indicated a presence. More directly, police descriptions of the group crossing certain intersections were contradicted by live traffic cameras showing those intersections, which showed no such thing.

But once again the apparent police intention of provocation via misinformation had been achieved. People at the CHAZ, already justifiably worried about violence, were put on high alert and armed themselves, producing a spectacle that even now persists on social media as a way to paint the entire protest with one brush.

The repeated amplification of individual images had some troubling commonalities, in particular the barely veiled parlance of racism. People in the protest zone and especially Black men, images of whom frequently accompanied these tweets and other posts, were invariably described as “thugs,” “savages,” “animals,” “feral,” and all the rest. Tellingly, those employing this vile lexicon were seldom Seattle or Capitol Hill residents; Twitter is very efficient at importing hate.

Indeed it did not take long for the CHAZ, having achieved the dubious distinction of attracting what is called national interest, to become the target of coordinated interference, harassment and disinformation campaigns by people all over the country. The resulting mess is a concise illustration of the incredible promise and complete inadequacy of online platforms in times like these.

The number of people and groups involved in these protests had made Twitter, with its accessibility and relative permanence, an invaluable tool for the dissemination of important information. While private groups on Signal, WhatsApp and Discord were also used, it was clearly better for things like police positioning, march updates, attacks on protestors and other crucial live communications to make the information as prominent and public as possible.

“There was a lot of momentum being built up, people learning and educating themselves. So this was the chance to finally put everything we’d learned into action.”

TK and her fellow organizer Tatii explained that social media was at the heart of their work, though the end result of taking to the streets was always the ultimate goal.

“Social media is a huge part because without it, we can’t do shit,” Tatii said bluntly. “When it comes to finding the information that we need and finding resources to help Black people, all of that is through technology. That’s how we network with people, that’s how people reach out to us. That’s how we get people telling us about police scanners. There are a lot of group chats, like with our medics, our car brigade, our bike brigade. It’s all through social media.”

“Scouts let us know if like there’s 30 bike cops coming down Broadway. It’s crucial when you are trying to strategically plan around that type of stuff, to keep from being cornered and boxed in,” said TK.

“At least on the Black side of social media, it’s constantly been talked about, Black Lives Matter,” added Tatii. “There was a lot of momentum being built up, people learning and educating themselves. So this was the chance to finally put everything we’d learned into action.”

It’s easy to take Twitter for granted, so we should be sure to give the platform due credit for the fundamental capability it provides. Many I’ve spoken to here emphasized that they trusted what they read from accounts with a verifiable track record more than what they saw in the perennially out-of-date local news. In fact, as Tatii and TK noted, many of their fellow organizers came to Seattle specifically to learn for themselves the truth behind mainstream reports that didn’t pass a gut test.

But the choice to publicly organize via hashtag, for all that it made important information available quickly to as many people as possible, had two major consequences.

First, it fragmented that information almost to the point of usability: One never knew whether it was #seattleprotest or #seattleprotests, #seattleprotestcomms, #seatleprotest (yes), plain old #seattle, #defundSPD, or a handful of others. This was only exacerbated with the creation of the CHAZ, which birthed a dozen new hashtags of varying quality and population. Instagram provided powerful amplification effects but little verification or network building.

Twitter also exposed this stream of important information to eager antagonists across the country, who flooded those hashtags with abuse and misinformation. Posts with images from other or past protests were used to mislead or misrepresent the present ones, and pictures of police around the area from other times were used in an attempt to spook those who had learned to be wary of SPD’s presence. Fake names and events were publicized, fake demands issued and met, and fake accounts claiming to represent protestors or the zone.

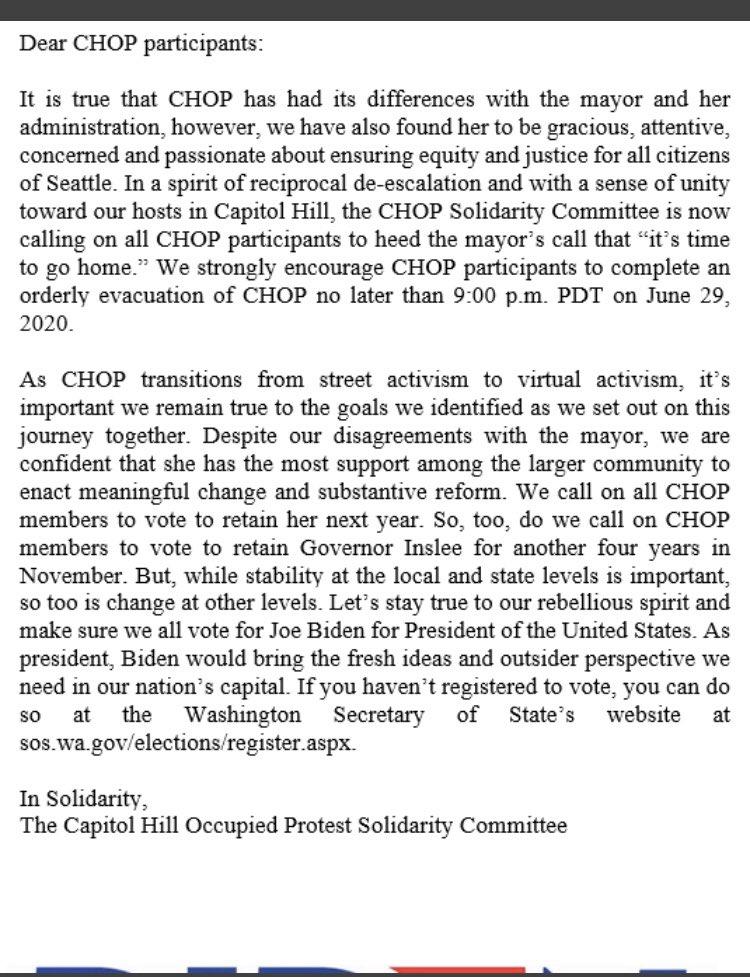

The ownership of one particular account was hotly contested, and confused by such tantalizing hints as it following Huawei leadership (you can imagine the theories this spawned), and for an “official” statement ending with what appeared to be a few stray pixels from a Biden presidential campaign graphic.

Later, when attempting to provoke a “mission accomplished”-style early exit from the zone after the Mayor cut $20 million from the police budget, the account exhorted its readers to vote for Biden. Needless to say this was not among the commonly agreed-upon demands or positions of the protests. Unless whoever was behind this strange yet prominent account exposes themselves, we may never know if it was a government plant, an agent provocateur or a practical joker, or what their intentions really are.

The enduring, chaotogenic myth that the CHAZ was an attempt to secede and form a socialist, anarchist utopia led to rebranding efforts. The misconception had become so widespread that it was decided to “officially” (as far as that concept existed in the space) change the name to the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest — then, noting the fact that Seattle itself is an “occupation” of native land, change the O to Organized.

This led to a further fragmentation of information channels: No one on the ground wanted to use #CHAZ and its relatives because it was no longer what organizers wanted to call it. But the name had entered the common parlance. So posts now needed to be #CHAZ, #CHOP, #CHOPCHAZ, and others like #CHAZSeattle and so on. It became very difficult to track an event — be it positive, like a march or speaker, or negative, like a fight or shooting — never knowing where to look or how to parse the information there.

It’s hard to overstate how effective the fractured narrative and opposing efforts were at shaping the national and global understanding of events surrounding these protests.

As they say you can never step into the same river twice, so it was on social media around the protest and the zone. The ever-shifting flow of Twitter sometimes produced absolutely vital data unavailable anywhere else, but always polluted with incomplete or premature judgments, ignorance, racism and false reports.

When I asked what digital tools were needed to better organize and avoid interference, protestors I spoke with generally said some sort of centralization and interoperability. Being able to colocate multiple feeds, authors, videos, images and static links in a dynamic, accessible way would save them huge amounts of time and effort. Certainly it would have helped to alleviate some of the problems noted above.

Stream of conscience

“Live streaming and having our phones out every single day is our best form of self defense.”

Although the technology has risen to mainstream popularity as a new form of passive entertainment on Twitch and other live platforms, it quickly became clear that it was the technology of choice for documenting these and other protests and social movements.

As TK put it: “People are visual learners; until they see it for themselves they don’t really believe it. And when it’s live, it’s live. You’re not seeing the cut, clipped and edited version. You can’t dispute what you see in raw live footage. You can’t ignore it.”

In Seattle, two people have become familiar faces, or voices, as they have doggedly documented every step of the protests this way, from before the CHOP to well after: Omari Salisbury and Joey Wieser.

Salisbury runs Converge Media, an independent web-distributed news organization. He comes from a broadcast and networking background, and when the CHOP emerged literally outside his doorstep — the studio door opened onto the police line before officers left — he took the opportunity to share the story, as objectively as possible. To him, the only tool that fit the bill was live streaming.

“The viewer needs to be able to see the context, because if the viewer can’t see the context, then it becomes something else,” he said. “People appreciate us because the stream is long, we keep the camera there and we let people make their own decisions.”

He was there not just for the controversial or terrifying moments, like clashes between provocateurs and protestors, or the shootings that occurred later on, but for the huge number of peaceful hours when people would share their own experiences at Salisbury’s prompting. The result is an incredibly valuable archive of hundreds of hours of live footage, ground truth from inside the zone that has been watched by millions.

Joey Wieser has no media background, but rather just a passing familiarity with the systems and social media methods that can grab people’s attention. Yet his stream came to be relied on by many, and the events he captured also racked up millions of views, simply because he decided to take advantage of the tools at his disposal.

“Live streaming and having our phones out every single day is our best form of self defense. Every day that I walk out my doorstep, I hold my phone as if it is my ultimate shield, my ultimate weapon,” he said. “Without it, I feel like I don’t have a role in this movement. It’s not like I’m some prolific live streamer, or that I know what Black communities need best. I’m just some white guy and I happen to work in tech. Having an understanding of what social media best practices look like, understanding analytics and social amplification — that combined with my community activism allowed me to come out here and do this.”

For Wieser, having the right connections or network was less important than being in the right place at the right time, even if it put him in danger. (He and Omari were both tear gassed multiple times and near shootings and other altercations.)

“I think it really puts the viewer at home in the driver’s seat,” he said. “Because they’re able to not only watch an uninterrupted stream, but to engage and have a real live conversation with somebody that’s there on the ground. You know, they can say, hey, turn to the left. What was that? It’s a participatory experience in a way watching the news doesn’t allow.”

One such incident I saw play out almost defies belief. Wieser was streaming the protest when a truck blasted through, nearly hitting several people. Minutes later, a person watching the stream was surprised when that very truck pulled up outside their apartment — it was their DoorDash driver, who announced proudly that they had just run down some protestors. (The driver’s plates and info were quickly sent through the proper channels.)

Being a two-way medium, it provides new opportunities for interference as well as engagement. Both Salisbury and Wieser experienced repeated attempts to pollute their comment sections or attack them personally.

“It’s not lost on me that this amplification can be used against us, but I think one of the important things about live streaming is that you can inject your own narrative, rather than let it be to the whim of, you know, Fox News or Sinclair,” said Wieser. “Regardless of whether or not the trolls take it over in the comment sections or in the hashtags, if you’re actually listening to the content, and if you’ve got someone out here who has the right heart and the right passion and the right analysis, you can reclaim that narrative.”

“The citizen journalist has always existed. They just never had the tools to be on equal footing with national news.”

“People rock with me because just turning on the camera and streaming, it’s not enough. Knowing the history of Seattle, the history of the neighborhood, understanding political positions… and you got to put paint where it ain’t, you know what I’m saying? The citizen journalist has always existed. They just never had the tools to be on equal footing with national news,” he said.

“People underestimate the tech that’s out there, especially the free stuff,” he continued. “I know people have their views about platforms and privacy. And I think that’s a different discussion. But I will say that what’s going on here allows for citizen journalists to touch the world. I used to build OTT and streaming platforms in Europe and across Africa. So understanding the actual technology that goes into this, man, I really don’t take no stream for granted. I’ve got people in Australia who’ve been on since day one. What if I had to cultivate that through my own contacts, do my own server, do my own everything? How would I reach them? It doesn’t work that way.”

He credits live streaming with putting pressure on local and national outlets to up their game, as well — being showed up by one person with a phone doesn’t look good for a major news organization.

“Citizen journalists and streamers came out here and forced the local media to change their whole game,” he said. “I mean, a guy with a cell phone didn’t get no respect back in the day. But I had my interviews with the mayor before anybody, my interviews with Chief Best before anybody. You see what I’m saying? I’m just a guy with a phone. Now the Seattle Times has a streamer out here. This situation has made the media adapt new technology.”

While live broadcasts have been part of local and national news for decades, it was in truth a totally different medium. But it’s now difficult to imagine coverage of events like these without modern live streaming, and legacy media have begun to recognize that.

Technology has always been a double-edged sword. The events in Seattle and across the country have illustrated this powerfully, and it seems unarguable that whatever happens in terms of policy and politics, the nature of protesting and the power dynamic that has defined it for decades has begun to change.

Ultimately, though, the power does not belong to the tech, but to the people.

“Technology plays a big part in all this, but I’m gonna be real with you, what you need is more old fashioned beating your feet to the streets,” concluded TK. “It’s not that the technology is insufficient, but that people are choosing not to use technology to understand.

“We’ve proven it time and time again that the only ones that really got our back is us.”

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/32te4dj

via IFTTT

Joey Wieser

Joey Wieser

Post a Comment